Blood tests could help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s disease more quickly and accurately, but not all tests are equally effective. Detecting memory problems caused by Alzheimer’s typically requires confirming the presence of beta-amyloid, a sticky protein, through brain scans or spinal taps. However, many patients are diagnosed based on symptoms and cognitive exams due to the challenges of obtaining these confirmatory tests. Labs are now offering various blood tests to detect signs of Alzheimer’s, but there is limited data on their reliability and little insurance coverage or FDA approval.

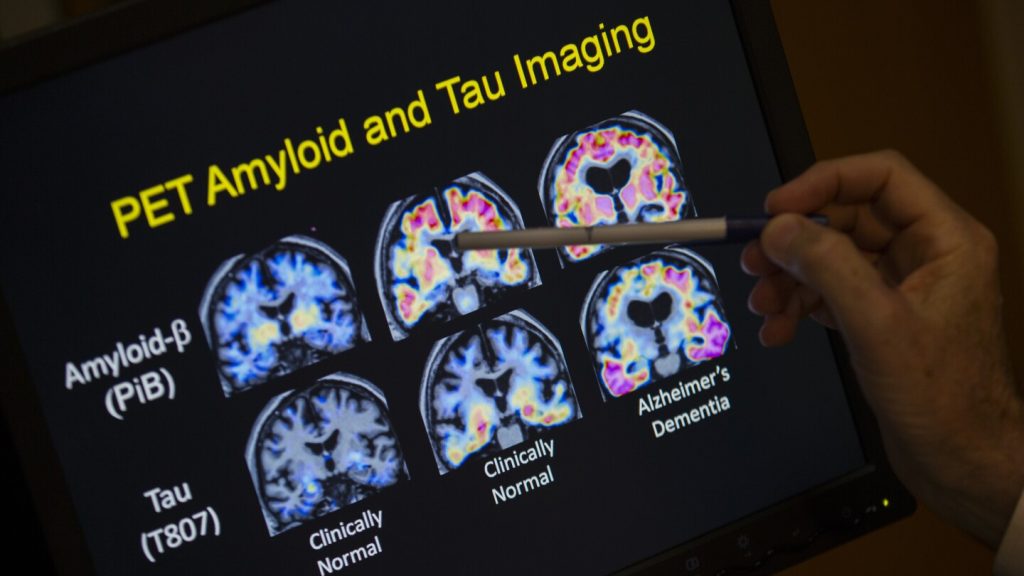

The demand for earlier Alzheimer’s diagnosis is increasing as more than 6 million people in the US alone have Alzheimer’s. The disease is characterized by brain-clogging amyloid plaques and abnormal tau proteins that lead to neuron damage. New drugs like Leqembi and Kisunla can slow the progression of symptoms by removing amyloid from the brain, but they are only effective in early stages of the disease. Confirming eligibility for these drugs can be difficult due to the invasive nature of spinal fluid tests and the cost and availability of PET scans.

A recent study conducted in Sweden involving 1,200 patients showed that blood tests for Alzheimer’s could be faster and more accurate than traditional exams. Primary care doctors, who see more patients with memory problems than specialists, could benefit from these blood tests. The study found that the accuracy of blood tests in diagnosing Alzheimer’s was significantly higher compared to initial diagnoses by doctors. The primary care doctors’ initial diagnosis accuracy was 61%, while the specialists’ was 73%, but the blood test was 91% accurate.

Different companies offer a variety of blood tests for Alzheimer’s, and it can be challenging to determine which ones are the most reliable. Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer Maria Carrillo recommends using tests with greater than 90% accuracy rates, such as those that measure p-tau217. This type of test correlates with plaque buildup in the brain, indicating a high likelihood of Alzheimer’s if levels are elevated. Several companies are working on developing p-tau217 tests, which could be beneficial for early detection of Alzheimer’s.

Doctors can order blood tests for Alzheimer’s from labs, but guidelines are still being developed regarding their proper use. For now, Carrillo advises using blood tests only in individuals with memory problems after verifying the accuracy of the specific test. Primary care physicians could benefit from these tests to determine who should be referred to memory specialists. Additionally, the tests are not recommended for individuals without symptoms but concerns about Alzheimer’s in the family, unless part of a research study. Prevention steps for Alzheimer’s remain limited, but ongoing studies are exploring potential therapies, some of which include blood testing.

Overall, blood tests for Alzheimer’s show promise in improving the accuracy and speed of diagnosis, particularly for primary care doctors who lack tools for evaluating memory problems. The development of reliable blood tests could aid in early detection of Alzheimer’s and potentially lead to better outcomes for patients. Researchers and companies continue to work on refining these tests, with the goal of obtaining FDA approval and establishing clear guidelines for their use in clinical practice.