Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs

Skift Take

Arthur wrote that “We are the first generation in human history to be able to travel to other continents as easily we once took a trolley to the next town.” Thanks to him, we could do this without having a ton of money, and hopefully walked away with a better trip because of that.

Jason Clampet

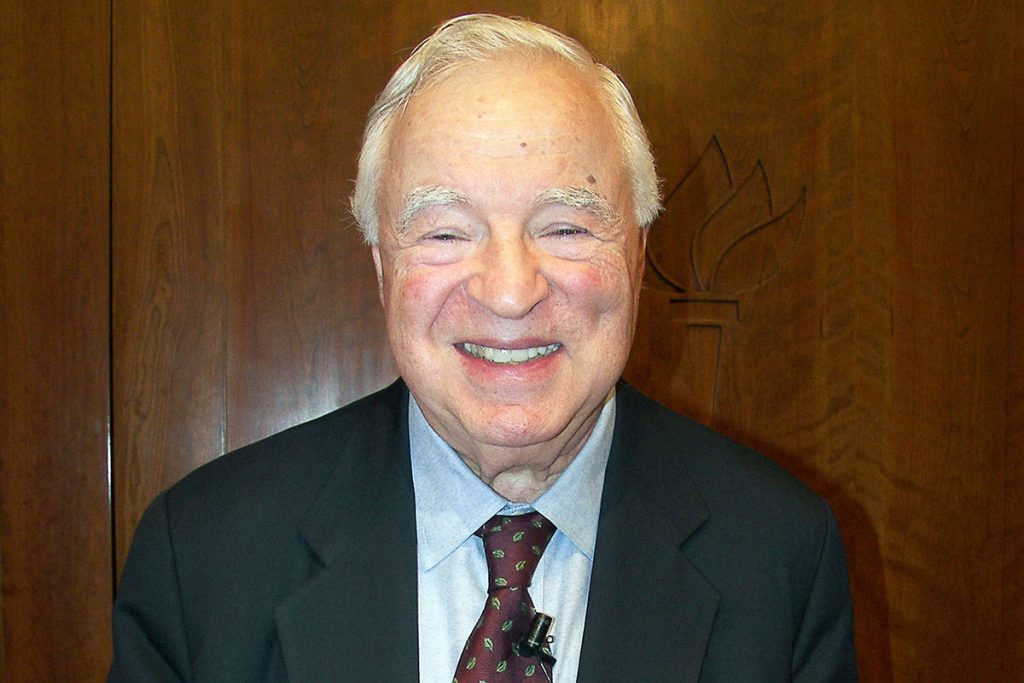

Budget travel pioneer Arthur Frommer passed away yesterday at the age of 95, his daughter Pauline Frommer wrote yesterday afternoon.

As an active-service officer with the United States military working in Europe in the post-World War II years, he self-published his GI’s Guide to Traveling in Europe in 1955. It became the prototype for every English-language guidebook series that followed, from Lonely Planet to Let’s Go to Rough Guides, and more. He turned the follow-up, the seminal Europe on $5 a Day, into a brand and then a publishing empire that’s now run by his daughter.

The GI guide came about because, as a soldier, Arthur realized that when he had a few days off, he could hop on a military transport plane and be in a different European destination in a matter of hours. He took advantage of this benefit, and then he told his colleagues and then the world how they could do the same.

For the next 70 years, he kept telling people where they might enjoy a great experience outside the comforts of home.

This was not a straight path. Arthur was a first-generation American. His mother and father were recent immigrants to the U.S. who met at a Jewish Social Club in Syracuse, New York.

He grew up in Jefferson City, Missouri, and then moved to New York City with his family when he was in his teens. He graduated from New York University in 1950, got a law degree at Yale, and was then drafted into the military, which oddly led to his career as a travel pioneer.

Frommer’s Impact

After the success of Europe on $5 a Day, things moved quickly. Multiple books in the series followed as both dollar amounts and geographic regions expanded. In the meantime, he built four hotels and started a tour company.

For Arthur, the focus was always on value. After the success of his first self-published book, Frommer remained steadfast in his devotion to budget travel even as he became a successful publisher and expert on travel.

Frommer on whatever-dollar-a-day became a mainstay for three decades. For anyone looking at the travel guidebook lineup in a library or a bookstore, the numbers in the titles showed what world was possible for American travelers venturing abroad.

His travel guide brand changed hands multiple times from the late 1970s, starting with Simon and Schuster and finally to Google in 2012 before he got the name back in 2013.In between, Arthur had a local and then syndicated radio program in New York City and beyond. He launched Frommers.com in 1997 and then started Arthur Frommer’s Budget Travel Magazine, which ran from 1998 to 2012.

Upon the 50th anniversary of Europe on $5 a Day in 2007, Frommer began a daily blog at Frommers.com, which he published every weekday for nearly a decade, with only a 6-month break between when Wiley sold Frommer’s to Google and he and his daughter Pauline Frommer retained rights to publish under the brand name.

Beyond the Pages

Before Rafat and I started Skift, I worked with Arthur every day for about five years at Frommers.com, then owned by John Wiley & Sons. It began with a week’s worth of blog posts sent via fax from Columbus Circle in New York to Hoboken, NJ — and then re-typed. He had told the Frommer’s publisher “I want to do a blog,” and then he did it.

Arthur worked hard. As his editor, I would receive emails after 11 p.m. to let me know his blog posts were ready for the next day. Rarely did I get fewer than three posts a day, and they were never based on press releases. Two years after starting the blog, he rewrote and edited many of the posts into the book Ask Arthur Frommer.

He had favorite subjects. His enthusiasm for Oxford’s summer adult learning program — and others like it elsewhere — was as reliable as the calendar. Fiercely opinionated, Frommer didn’t hesitate to criticize businesses he thought were harming customers. And he was no fan of large cruise lines.

Despite his broad appeal across the U.S., Arthur didn’t try to make everyone happy and would speak out on issues that he found important. In the mid-2000s, that was a boycott on travel to Burma, for one.

In 2009, in response to armed men gathered outside of a talk by President Barack Obama in Phoenix, Arizona, Arthur wrote that the state’s open carry firearm laws in public places made him rethink future travel there. The next day a Fox News evening program did a segment on Arthur’s comments — death threats quickly came flooding in the form of comments on the blog post.

The digital team spent the weekend removing tens of thousands of user comments that promised to shoot or lynch Frommer and his family. Political leaders in Arizona proposed boycotts of Wiley books in schools in response. Three months after Arthur’s post, congresswoman Gabby Giffords was shot in the face at a political rally in Arizona.

Legacy

Arthur Frommer showed Americans how to travel to Europe better than anyone else. Over and over he emphasized that you didn’t have to be wealthy to experience the world, and you may just have a worse time if you did have a lot of money.

Now and then that would lead in a funny direction (he once told me eating at hospital cafeterias was a good idea since they were cheap because they were subsidized), but it nearly always opened doors for travelers that had before seemed closed.