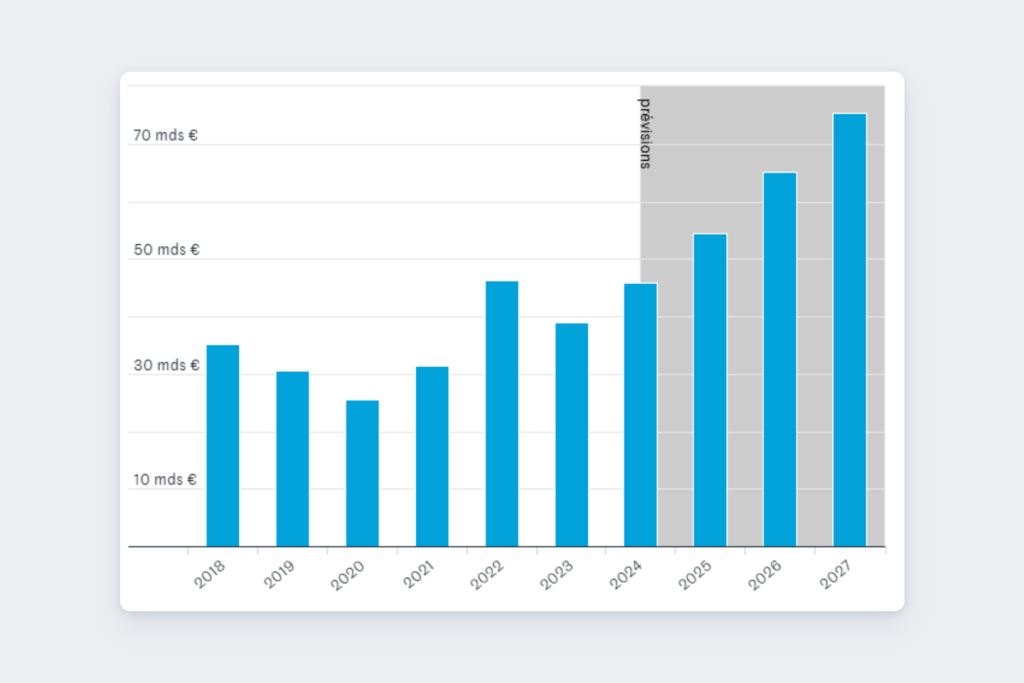

The discussions surrounding the 2025 budget in the National Assembly have brought the issue of public debt back into the spotlight. With the debt level at 112% of the GDP, concerns arise due to the increasing costs associated with repayment each year, compounded by interest. Predictions from Bercy suggest that the “debt burden” is set to significantly rise in the coming years, from 46 billion euros in 2024 to 75 billion in 2027. The rising costs are starting to impede the state’s ability to invest and could pose a risk in case of a macroeconomic shock.

The French state regularly incurs debt to finance public operating and investment expenses, borrowing, paying interest, repaying, and taking on new loans. Historically, France has used various forms of borrowing, such as appealing to savings from French citizens, whether voluntarily (the “Balladur loan” in 1993) or forcibly (Pierre Mauroy’s “forced loan” in 1983), or by imposing debt on banks. Currently, the country largely borrows from financial markets, with the French Treasury Agency (AFT) managing these operations by announcing financing needs to investors and allocating based on offers.

The annual debt service costs for France are considered one of the state budget’s expenditures, with projections indicating it will be the fourth-largest expense in public spending in 2025, surpassing budgets for security or ecology, but behind education, defense, and tax refunds. The budget allocated to debt repayment has significantly increased over the years, pointing towards a potential rise to 75 billion euros in 2027, equating to 2.4% of the GDP.

The increase in debt service costs can be attributed to various factors, such as inflation surges from 2022-2023, contributing to higher variable interest rates tied to inflation for state loans. Additionally, rising general interest rates over the years have led to France borrowing at around 3% currently, compared to 0% in 2021. The debt’s growth over the past decade has also contributed to escalating debt service costs in a cycle where borrowed money goes towards repaying interest, thereby increasing debt further.

Concerns over the sustainability of France’s debt are raised, with worries over a potential inability to finance in the markets in the future. The level of debt sustainability largely hinges on market confidence in France’s repayment ability, influenced by factors like credit rating agency evaluations. Moody’s recent alert to France highlighting public finance deterioration raises questions, but the country still manages to secure favorable interest rates for new loans due to its perceived financial stability.

While France’s debt situation remains manageable for now, political uncertainties and budget controversies have led to increased borrowing costs compared to neighboring countries. The risk primarily centers on the financial burden of debt repayment, urging governments to reduce spending on other public sectors or increase taxes to cover interest payments. This budgetary struggle has sparked debate between parties, with the right advocating for spending cuts and the left fearing austerity measures could hinder economic growth and worsen deficits. Proposed solutions such as debt cancellation have also been suggested but come with their own risks.