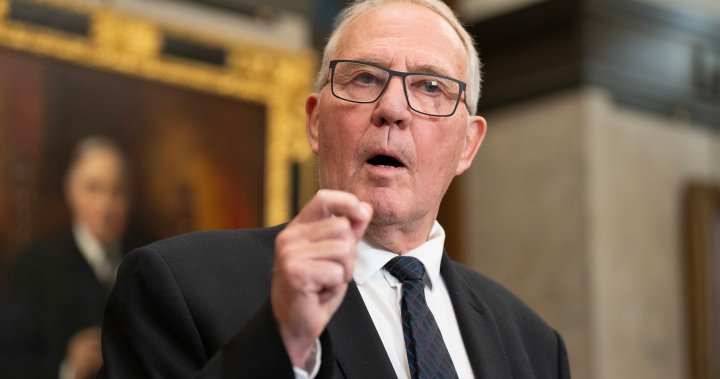

Former public safety minister Bill Blair was not advised for weeks after CSIS informed his chief of staff that they were seeking approval to investigate Ontario Liberal powerbroker Michael Chan in March 2021. The delay of more than a month before Blair signed off on the warrant application targeting Chan remains unclear, especially in the lead-up to the 2021 federal election. Chan, a notable figure in Liberal circles in Ontario, has been suspected of having close ties to the Chinese consulate in Toronto and PRC proxies in Canada, claims he has denied. Requesting to surveil a prominent politician is an unusual occurrence and requires approval from a federal judge, senior CSIS officials, and the minister of defence, which Blair currently holds.

The federal inquiry into foreign interference has not provided a concrete explanation for the delay in approving the warrant to surveil Chan. Blair stated that while it was appropriate for his staff and CSIS to ensure submissions were correct before bringing them to him, his expectation was for warrant applications to be processed promptly. Zita Astravas, Blair’s former chief of staff who was briefed by CSIS on the warrant in March, did not respond to inquiries. The current deputy mayor of Markham, Michael Chan, is suing CSIS over leaked information and two reporters. Typically, CSIS allows a 10-day window between delivering a warrant for the public safety minister’s approval and receiving a decision. However, the delay in this case was significantly longer, causing frustration among CSIS officials.

Former CSIS analyst Stephanie Carvin, who now teaches at Carleton University, explained that investigating politicians is a sensitive matter for the agency due to past controversies and concerns about privacy. The process of obtaining a warrant for surveillance involving politicians includes significant involvement from high-level CSIS officials, potentially even the director. Actively surveilling a politician requires approval at the highest levels and a substantial allocation of resources. Carvin emphasized that obtaining a warrant and collecting information is not a straightforward process for CSIS, and once they decide to pursue surveillance, it signifies a serious concern that warrants significant resources and attention.

Justice Marie-Josée Hogue’s foreign interference commission heard evidence that CSIS briefed Blair’s chief of staff on the warrant in early March and delivered it to the office shortly after. The delay in approving the warrant was a cause of frustration for CSIS headquarters, regional offices, and agents monitoring Chan. Despite the delay, former CSIS director David Vigneault was not concerned, and Blair approved the warrant on the same day it was brought to his attention. The agency’s work in preparing a warrant application involves thorough research and considerations due to the sensitive nature of surveilling individuals in sectors like politics.

The involvement of CSIS in seeking approval to surveil a politician like Michael Chan reflects the heightened scrutiny surrounding foreign interference in Canadian politics. Chan, a former provincial cabinet minister with ties to China, has faced suspicions of working closely with Chinese officials and proxies in Canada. The process of obtaining a warrant for surveillance in such cases is complex and requires careful consideration at all levels of the agency. The delay in this particular case raised questions about the decision-making process within the agency and the role of the public safety minister in approving sensitive surveillance operations. The ongoing federal inquiry into foreign interference will continue to shed light on this incident and its implications for national security and political integrity.