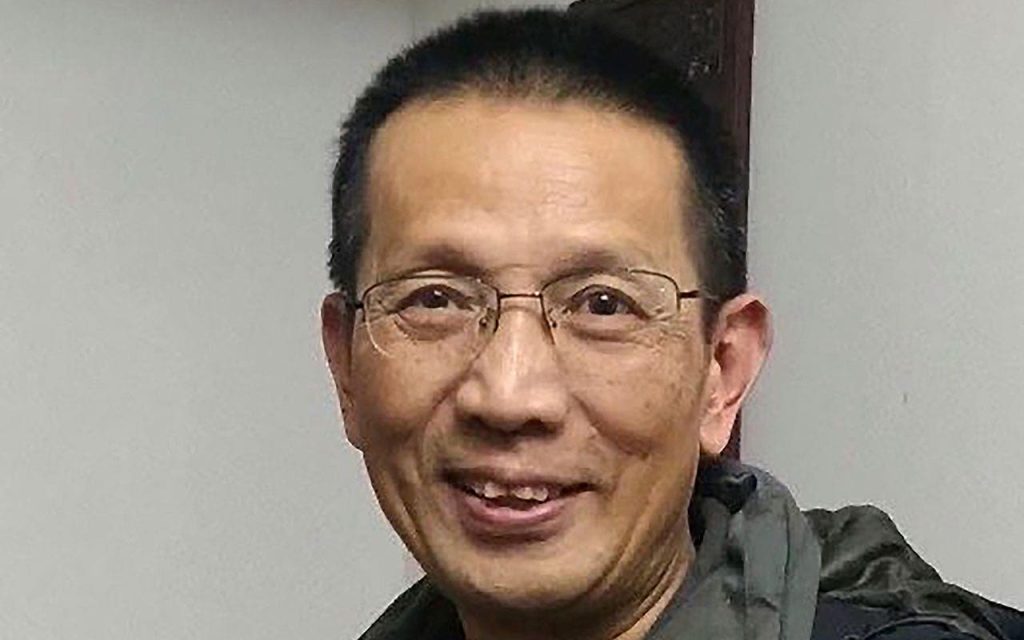

Rev. John Sanqiang Cao, a Chinese pastor, has faced significant challenges following his release from prison. Cao was arrested and sentenced to seven years in prison while returning from a missionary trip in Burma. Despite being released, Cao has found himself without legal documentation, making it difficult for him to access basic services such as buying a train ticket or seeing a doctor. He described feeling like a “second-class” citizen due to the restrictions placed upon him.

Born and raised in Changsha, Cao dedicated his life to spreading Christianity in China, where the religion is strictly regulated. He studied in the U.S., married an American woman, and started a family before returning to China to spread his faith. Operating outside of state-sponsored churches, Cao faced risks as Christianity was only allowed in approved churches where the Communist Party controlled interpretations of Scripture. Despite the challenges, Cao had a network of Bible study schools across the country and conducted relief work in northern Burma.

Following his arrest in 2017 on charges of “organizing others to illegally cross the border,” typically applied to human traffickers, Cao spent seven years in prison. However, his family and supporters were unsuccessful in having his sentence reduced. Even after his release, Cao now faces a new obstacle – the lack of a hukou registration, essential for obtaining a national ID card in China. A police officer mentioned that even though Cao went to prison, he should still have a hukou, indicating some confusion surrounding his case.

Cao did not take American citizenship due to his calling and split his time between China and the U.S. Keeping his U.S. permanent residency, he traveled on his Chinese passport but faced challenges due to the lack of hukou registration. Despite repeated attempts to address the issue with the police and hiring a lawyer, Cao has not received a satisfactory answer. His adult sons recently visited him in China, but Cao hopes to join them and his wife in the U.S., though the process remains unclear.

Though now a free man, Cao considers himself in a “bigger prison,” unable to navigate the bureaucracy without the necessary documentation. Cao’s case highlights the challenges faced by individuals in China, particularly those who engage in religious activities outside of state control. His commitment to his faith and mission has led to personal sacrifices, including his freedom. As he continues to advocate for his rights and pursue a solution to his legal status, Cao’s story sheds light on the complexities of religious freedom and human rights in China.