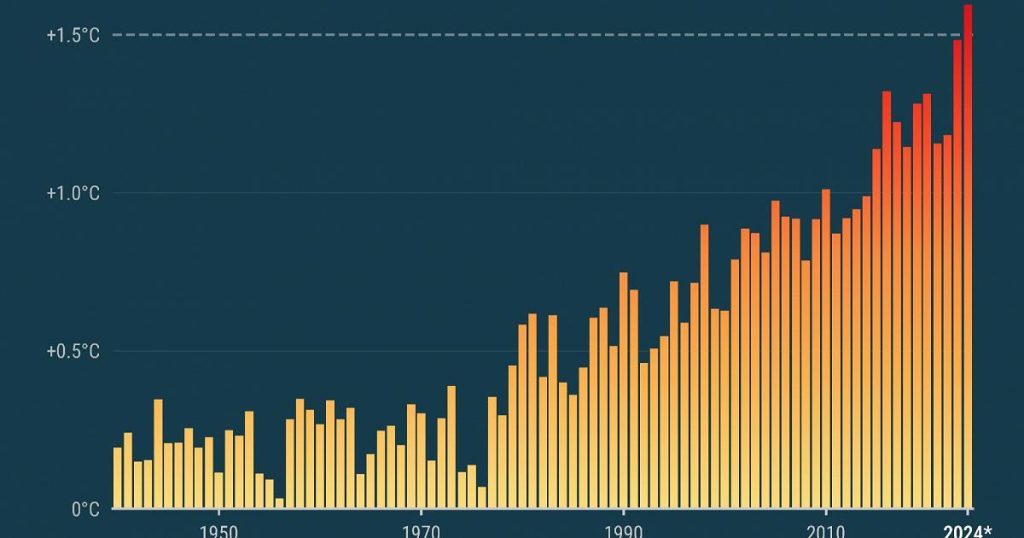

It is almost certain that 2024 will be the hottest year in recorded history, exceeding the +1.5 degrees Celsius threshold above pre-industrial levels. Data from the Copernicus Climate Monitoring Service of the European Union indicates that the global temperature anomaly for the first 10 months of 2024 has been 0.71 degrees higher compared to the 1991-2020 average, making it the highest on record for this period. Additionally, it is expected that 2024 will surpass the previous record set in 2023 by reaching more than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, possibly exceeding 1.55 degrees.

For the average person, an increase of 1.55 degrees globally may seem insignificant. However, when scientists consider this rise across the entire earth and its oceans, the amount of energy involved becomes significant and leads to an exponential increase in the frequency and intensity of destructive weather events like catastrophic floods that are being felt even in temperate latitudes. As the world approaches the climate talks at the United Nations, the Deputy Director of Copernicus, Samantha Burgess, believes that this record-breaking data should serve as a catalyst to increase ambition for the upcoming Conference of Parties on climate change, COP29.

Data collected by Copernicus shows that October 2024 was the second warmest October globally, with a temperature anomaly of 1.65 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The past 12 months leading up to October 2024 have seen a global average temperature increase of 0.74 degrees compared to the 1991-2020 average, estimated to be 1.62 degrees higher than pre-industrial levels. Europe saw temperatures well above average, with most of the continent experiencing warmer conditions. This trend was also observed in regions such as northern Canada, central and western United States, northern Tibet, Japan, and Australia.

In terms of sea surface temperatures, October 2024 marked the second highest global average on record, only 0.10 degrees Celsius lower than October 2023. While the eastern and central equatorial Pacific showed temperatures below average, hinting at a shift towards La Niña conditions, sea surface temperatures remained unusually high in many regions. The impacts of climate change on sea ice were also evident, with both Arctic and Antarctic sea ice extents reaching historically low levels, leading to disruptions in ecosystems and weather patterns.

The effects of these rising temperatures were also observable in hydrological variables, with regions such as the Iberian Peninsula, France, northern Italy, Norway, and northern Sweden experiencing above-average precipitation, leading to severe flash floods in areas like Valencia, Spain. Conversely, regions like eastern Europe, western Russia, Greece, and western Turkey saw below-average precipitation and soil moisture levels. The disparities in precipitation patterns were also evident on a global scale, with wetter conditions observed in parts of southern China, Taiwan, Florida (USA), western Australia, and southern Brazil, while drier conditions prevailed in most of the United States, central Australia, southern Africa, Madagascar, parts of Argentina and Chile, exacerbating drought conditions and impacting millions of people.