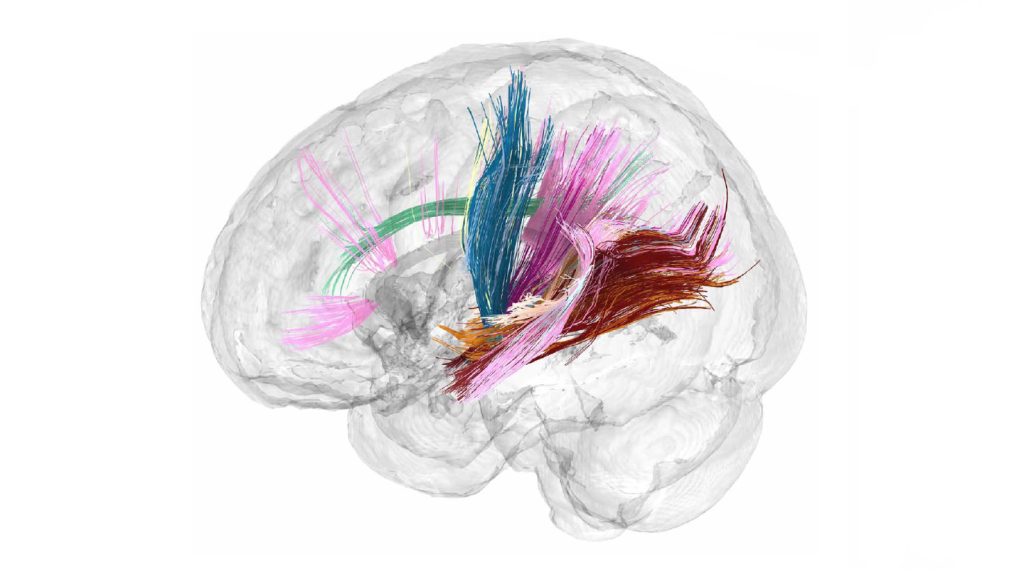

A recent study has shed light on the changes that occur in the brain of a pregnant woman. The research involved MRI scans of a woman before, during, and after pregnancy, showing a dramatic reduction in gray matter volume in about 80% of the brain regions studied. Despite the frightening idea of a shrinking brain, researchers assure that this process is not harmful and actually comparable to Michelangelo chipping away excess marble to reveal a masterpiece. Additionally, the study found that some white matter tracts in the brain actually grew stronger during pregnancy, peaking in the second trimester and returning to pre-pregnancy strength after childbirth.

The research on the changes in the female brain during pregnancy is a part of a growing body of work aimed at understanding the brain at different stages of life. Matrescence, the process of becoming a mother, has been likened to adolescence in terms of the significant changes it brings about in the brain. Previous studies had only compared brain scans before and after pregnancy, leaving a gap in understanding the changes that occur during pregnancy itself. The new study fills this gap by providing a detailed account of the brain changes that take place in a woman throughout the entire pregnancy journey, from pre-pregnancy to postpartum.

The study not only confirms previous findings of reduced gray matter volume after pregnancy but also delves deeper into the extent and magnitude of this reduction. Gray matter, which is mainly composed of cell bodies, saw reductions in nearly 80% of the regions studied, with an average of 4% reduction in volume. These changes, especially the reductions in gray matter, are thought to be permanent and can last for years after pregnancy. This highlights the need for more research into understanding the long-term effects of pregnancy on the brain, as the current understanding of these changes is quite limited.

The lead researcher of the study, Liz Chrastil, also a cognitive neuroscientist, had her own brain scanned throughout her pregnancy. Despite the changes observed in her brain, Chrastil reported feeling fine and experiencing no negative effects on her cognitive abilities. However, she acknowledges that there is much more to be learned about how pregnancy affects the brain, especially since women’s brains are still vastly understudied. The study raises more questions than answers, emphasizing the need for further research to fully understand the impact of pregnancy on the brain.

Overall, the study on the changes in the female brain during pregnancy provides valuable insights into how motherhood affects brain structure and function. By following one woman’s brain changes throughout pregnancy, the researchers were able to identify significant alterations in gray and white matter, shedding light on the complexity of the brain’s adaptation to motherhood. The findings not only contribute to the growing body of work on understanding the brain at different life stages but also underscore the need for more research to fully grasp the implications of pregnancy on brain health and function.