A long-term study investigating Havana Syndrome patients was recently shut down by the National Institute of Health (NIH) after an internal review board discovered mishandling of medical data and coercion of participants to join the research. The study had previously failed to find evidence linking the participants to the same symptoms and brain injuries associated with Havana Syndrome. The decision to halt the study came after complaints from participants about unethical practices and pressure to take part in the research.

Despite qualifying for U.S. government-funded treatment for their brain injuries, an interim report released by the intelligence community last year concluded that it was “very unlikely” that a foreign adversary was responsible for the symptoms experienced by hundreds of U.S. intelligence officers. The NIH investigation found that regulatory and policy requirements for informed consent were not met due to coercion, although not by NIH researchers themselves. A former CIA officer, known as Adam to protect his identity, expressed little surprise that the study was shut down, describing the study as dishonest and potentially criminal in nature.

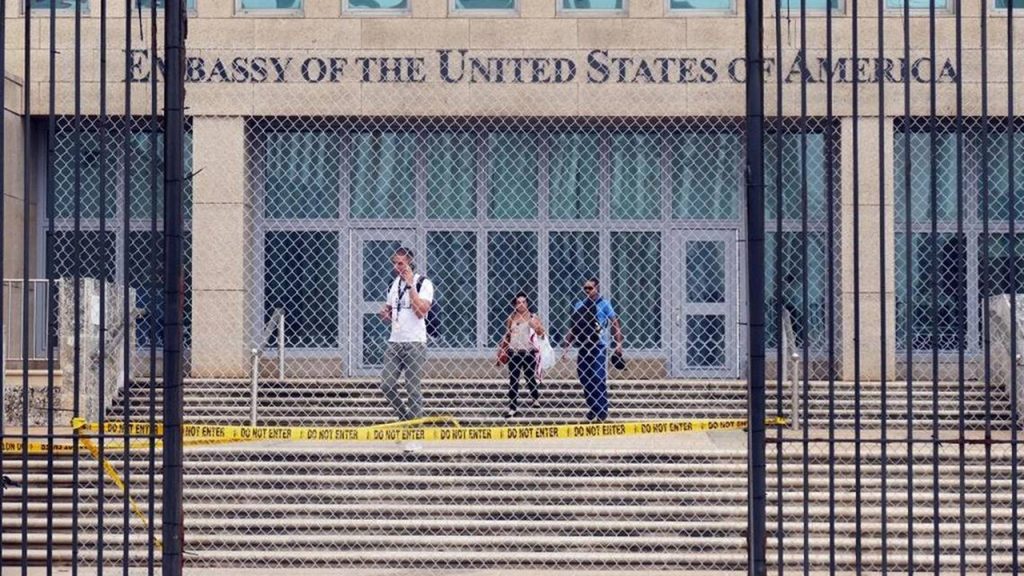

Adam, who is considered Havana Syndrome’s Patient Zero, was the first to experience severe sensory phenomena that have affected numerous U.S. government workers stationed overseas, including in locations such as Havana, Moscow, and China. Patients believe that the symptoms are caused by a pulsed energy weapon, leading to vertigo, tinnitus, and cognitive impairment. Despite the severity of the symptoms, the CIA has been accused of including patients who may not truly qualify as Havana Syndrome patients in the study, thereby compromising the accuracy of the data being analyzed by NIH researchers. Patients also reported pressure to participate in the study in order to receive treatment at Walter Reed.

The cooperation between the CIA and NIH has raised concerns among patients, with accusations of the CIA dictating which patients could participate in the study and providing inadequate control groups. The CIA has stated that they take claims of coercion seriously and have cooperated fully with the NIH review. However, patients affected by Havana Syndrome are now calling for the retraction of two articles published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) last spring. These articles used early data from the NIH study to conclude that there was no significant evidence of brain injury among participants compared to control groups.

The experiences of Havana Syndrome victims have raised significant concerns about the ethical practices surrounding the study of their condition and the potential involvement of government agencies such as the CIA. Patients like Adam have highlighted the need for transparency, accurate data collection, and proper treatment protocols to address the complex symptoms associated with Havana Syndrome. Moving forward, there is a need for accountability and ethical oversight to ensure that similar research efforts avoid the coercion and mishandling of data that led to the shutdown of the NIH study.