A recent study has shed light on the dental development of an early member of the Homo genus, revealing a unique pattern of growth that suggests an extended childhood may have been present. The fossil teeth of an 11-year-old individual from the Dmanisi site in Georgia show a slowed development of premolar and molar teeth up to age 5, followed by a rapid growth spurt. This slowed start indicates an initial step towards extending growth during childhood, different from the chimplike pattern observed in other species.

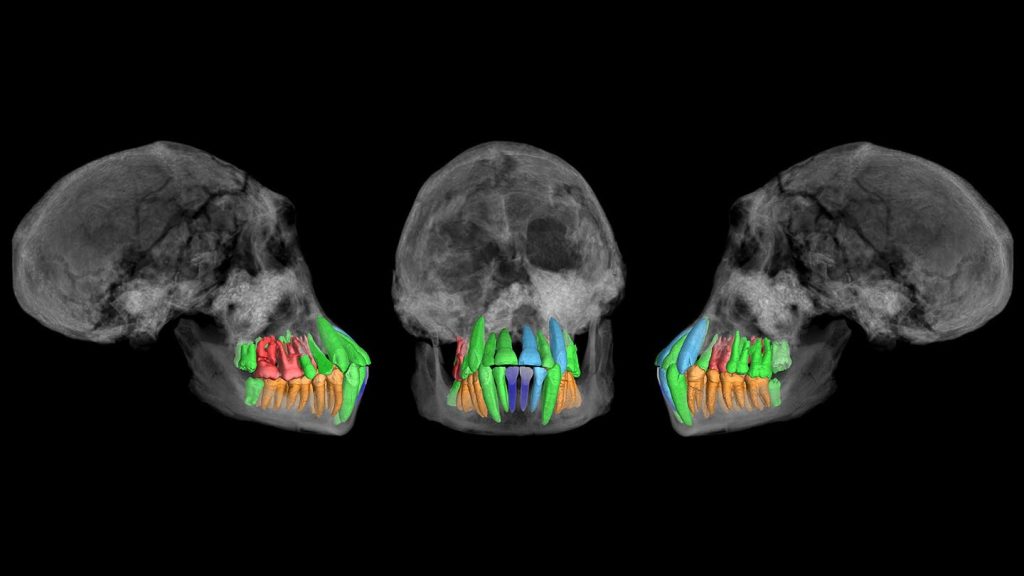

The researchers used X-ray imaging technology to examine microscopic growth lines inside the fossil teeth, providing a detailed insight into the dental development of the ancient individual. The Dmanisi specimens are dated to around 1.77 million to 1.85 million years ago and are classified as an undetermined Homo species by the researchers, rather than Homo erectus. This species had only slightly larger brains than modern chimps, challenging the idea that an extended childhood evolved alongside brain expansion in Homo sapiens.

The study offers the first comprehensive reconstruction of an ancient hominid’s dental development, highlighting the different growth patterns observed in early Homo species. The prolonged childhood observed in the Dmanisi youth could be attributed to shared childcare practices, including grandmothers and unrelated helpers. This extended childhood may have been an evolutionary experiment within the Homo lineage, leading to further changes in childhood growth as brain size increased in later Homo species.

While the study suggests a possible link between extended childhood and dental development in early Homo species, some experts caution against drawing definitive conclusions. Variations in available foods, age at weaning, and other factors could have influenced tooth development in ancient hominids, leading to diverse growth patterns even within the same species. Additionally, the timing of the first molar eruption in the Dmanisi youth suggests a chimplike trajectory, indicating rapid overall development rather than an extended childhood.

Paleoanthropologists have differing opinions on the implications of the study’s findings. While some argue that the chimplike dental features of the Dmanisi youth align with their small brain size, indicating rapid development, others suggest that shared childcare practices may have played a role in shaping the extended childhood observed in early Homo species. Further research and discoveries are needed to fully understand the evolutionary significance of extended childhood in the Homo lineage and its relation to dental development and brain expansion.